The first 100 days of the COVID-19 response: past investments in health security system pay off, and learning lessons for the future

On 27 January, Cambodia detected and confirmed its first case of COVID-19. Within 100 days, more than 2.5 million cases of COVID-19 were recorded globally with more than 200,000 deaths. During the same period, Cambodia detected and managed 122 cases, a comparatively small number next to the rest of the world. With zero COVID-19 related deaths and an absence of widespread community-level transmission to date, Cambodia has demonstrated an effective rapid response to the initial cases. A whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach, along with vigilant surveillance, laboratory, rapid response teams, and good collaboration between the Ministry of Heath and technical partners have all contributed to this successful response within the first 100 days. However, Cambodia is still at the early stages of the COVID-19 epidemic. Cambodia is making efforts to be alert and ready to respond to larger scale community transmission.

A Good Foundation

Over the last decade, with the support of WHO and partners, Cambodia has made important investments into the health security system in the country, which has enabled a robust response to the COVID-19 crisis. This capacity building has focused on the core systems of surveillance mechanisms that aim to detect and respond rapidly to infectious health threats and other acute public health events. This strengthened capacity was called into action when the first case was confirmed in Cambodia at the end of January 2020.

Cambodia’s surveillance system includes event-based and indicator-based surveillance; real-time databases and risk assessment mechanisms; rapid response teams (RRTs); field epidemiology training; national public health laboratory capacity; and platforms for risk communications. Cambodia’s health security system is led by the Communicable Disease Control (CDC) Department of the Ministry of Health (MOH) which also serves as the National Focal Point for the International Health Regulations (IHR 2005), a global system facilitated by WHO for information sharing, risk assessments, and coordinated and core capacity building. In the WHO Western Pacific Region, implementation of the IHR 2005 has been guided by the strategic framework called APSED III, the Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases and Public Health Emergencies.

Surveillance

Surveillance systems are essential for the early detection of cases and collection of epidemiological information that allows the analysis of risk of infectious disease spread in order to guide appropriate public health actions. Cambodia’s existing surveillance and response systems contributed to the rapid COVID-19 response in the first 100 days after COVID-19 was first identified in Cambodia. The decisive detection, confirmation, isolation and treatment of the first case within four days of his entry from China on 27 January, highlights this achievement.

Since then a further 121 cases (for a total 122 cases, comprising of 38 women and 84 men) have been identified between late January and April 2020. Most have had mild or no symptoms, and there have been no deaths in the Kingdom of Cambodia. Over two-thirds of the cases (85) were considered imported as a result of infection acquired outside the country, and the rest were linked to one of these imported cases. Cases were detected in 13 provinces including the capital, Phnom Penh, affecting people of eight nationalities in addition to 34 Cambodians. On 21 and 22 May, two additional cases were identified in travellers – one was the result of a new policy to screen and test all arriving passengers from international destinations and the other developed symptoms during their quarantine.

When WHO raised the alarm on a novel coronavirus identified in Wuhan, China, CDC/MOH immediately activated the surveillance and response system to be on high alert for people with respiratory symptoms (e.g. fever, dry cough, difficulty breathing) and a history of travel from China. The points of entry system, which involves quarantine officers at airports, ports and ground crossings, was enhanced to screen passengers for fever using thermal scanners, provide information about symptoms and care-seeking via distribution of health notice forms and posters, and collect health declaration cards.

Cambodia’s early warning and response system, called CamEWARN, is an indicator-based system that collects aggregated information on seven disease syndromes, including respiratory infections, from all public health facilities in the country. In addition, the event-based system includes daily media monitoring for any reports and a national toll-free 115 hotline that the public can call to report suspected events in the community. The phones are manned by the rapid response teams (RRTs) spread across all 25 provinces. As a result of the COVID-19 outbreak response, the 115 hotline has been scaled up to respond to an increased number of calls and can now handle up to 10,000 calls if needed. The number of daily calls ranged from 600 to over 2,000 during the first 100 days of the outbreak.

Laboratory Diagnostics

Reliable, accurate and timely laboratory diagnostics are critical for mounting an appropriate response to COVID-19. In Cambodia, an effective specimen management system ensures samples are collected from suspected cases and referred to a designated COVID-19 testing laboratory for real-time testing to support case investigation, contact tracing and clinical management. The Institute Pasteur Cambodia (IP-C) and the National Institute of Public Health are the main testing labs while the U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit-2 Detachment provides surge capacity. All testing and clinical care has been made available for free by government decision, as an important contribution to an equitable response and access for all, and also as a major contributor to ensuring outbreak control.

IP-C has recently been designated a WHO global referral laboratory for COVID-19 and provides reference functions such as assay validation, capacity building, data management and analysis, and culture and sequencing of the virus. To date, over 14,000 samples have been tested in Cambodia.

Contact Tracing

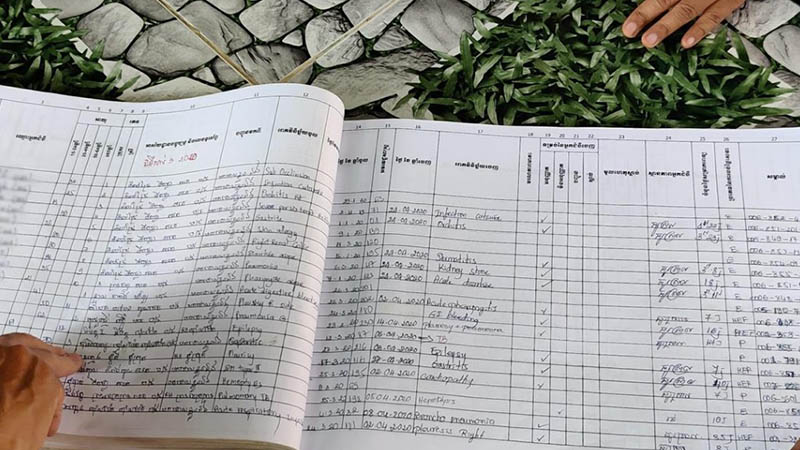

The RRTs are comprised of 2,910 trained public health staff at national, provincial, district and health centre levels. They are responsible for investigating and verifying reported calls to the hotline. This, however, is only one of their roles. They have also undertaken contract tracing including for five “clusters” or groups of linked COVID-19 cases.

Contact tracing is the process by which people who have been in contact with laboratory confirmed COVID-19 cases are first identified through a detailed record of the case’s movements during the infectious period before they showed symptoms. These contacts are then encouraged to self-quarantine by staying in one place and refraining from direct contact with others, during which time their health is monitored daily.

As advised by WHO, contact tracing and management is the key public health strategy during the early phase of the response efforts when containment of the epidemic is possible. As cases are confirmed, the provincial health departments and RRTs are mobilized to locate the case and interview them about their movements during the 14 days before diagnosis and to draw up a list of possible contacts. It is medical detective work.

National surveillance team collecting samples from a high-risk group

RRTs take detailed information on these contacts’ movements. Close contacts are quarantined for 14 days, during which they may develop symptoms if they are infected. Samples from nose and throat are collected from close contacts and tested on the first and 14th day for COVID-19. Other contacts have no restrictions imposed on their movements but are monitored for 14 days to see if they develop any respiratory symptoms.

This has been a laborious process with over 2,300 contacts traced and 27 new cases identified by the RRTs and national team based at CDC/MOH.

Cluster Management and “Hotspot” Hunting

During the course of the first 100 days of the pandemic in Cambodia, the MOH’s surveillance and response system has been supported by WHO, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, IP-C and other technical partner agencies to ensure containment of the spread of COVID-19. In these first 100 days, five major clusters of the disease were identified, which means that a number of COVID-19 cases are associated with exposure to the same source of infection.

The first of these was the Viking Mekong river cruise which came from Vietnam with three positive cases, plus a further four cases among the close contacts who were quarantined in Kampong Cham Province. A second group consisted of 34 cases who acquired COVID-19 as a result of attending a large religious gathering in Malaysia, and then passed it on to an additional nine close contacts across 12 provinces. A third cluster comprised 31 positive cases amongst a French tour group in Preah Sihanouk with a further eight cases amongst their close contacts. The fourth group was the result of one case acquired in Thailand who passed it on to four additional contacts. The fifth cluster was associated with a returning Chinese traveller from Guangzhou who transmitted the infection to four individuals with whom he had close contact.

The approach of “hotspot” hunting to conduct pre-emptive specimen testing amongst possible contacts in a focused geographic area is a form of modified contract tracing which was employed to ensure a thorough search for possible additional contacts. Each of these clusters of cases could have easily resulted in a much wider spread of COVID-19. But this did not happen. This is in no small part because of intensive contact tracing management by Cambodia CDC/MOH-led surveillance team who, on a daily basis, diligently contacted and followed up on hundreds of those who were exposed to the cases of COVID-19.

Existing Surveillance Systems as the Foundation

In addition to the surveillance systems for emerging diseases already described, there is also a long-established influenza surveillance system that identifies influenza (ILI) and severe acute respiratory illness (SARI) cases at 15 hospitals around the country. This is part of the global influenza system, managed by WHO called the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS), which aims to quickly detect cases of respiratory disease that may subsequently develop in to a larger outbreak.

The symptoms of influenza and COVID-19 are similar, and so influenza surveillance has been integrated so that all influenza samples are also tested for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. These systems together provide an overall picture of transmission of infection in the community. Any changes in the numbers of 115 hotline calls, trends in reported respiratory cases or COVID-19 positive specimens can be information for early indicators of community-level spread of the disease, which can then be used to inform the next phase of the response.

A Coordinated Response

Sub-committee on COVID-19 members meet with a private clinic

Cambodia has been working hard to prepare for and respond to the COVID-19 pandemic beyond the surveillance system. The country has made great efforts in mobilizing a whole-of-government and a whole-of-society approach under the leadership of Samdech Prime Minister, including the establishment of national and provincial multisectoral committees to combat the pandemic. Under the leadership of the Health Minister and with the support of WHO and partners, the National Master Plan has been developed to prepare for a potential large-scale community transmission scenario. Priority actions in nine key areas (incident management and planning, surveillance and risk assessment, laboratory, clinical management and health care services, infection prevention and control (IPC), non-pharmaceutical public health measures, risk communication, points of entry, and operational logistics) have been identified and are being implemented in line with WHO recommendations and in collaboration with many partners.

100 Days Later

Cambodia’s effective rapid response to the initial 122 cases (as of 20 April) and the fact that the country has not seen widespread community-level transmission of COVID-19 to date can be attributed to the hard work of the surveillance and laboratory teams, and RRTs who have quickly identified and diagnosed cases and closely followed-up their contacts to prevent further spread of the virus. The investment of many years in strengthening the health security system in Cambodia contributes to this successful containment effort. It has bought the rest of the health system, and the society, time to better prepare for a potential larger outbreak of COVID-19. The fact that there have been no healthcare worker infections or health facility outbreaks in the first 100 days speaks to a good implementation of IPC and clinical management at health care facilities.

COVID-19 is a new disease with many unknowns and there remains great uncertainty as to how the pandemic will eventually play out around the world. The learning and experience from the first cases of COVID-19 in Cambodia have strengthened the country’s capacity for future containment and mitigation efforts. It is vital for Cambodia to continue to strengthen multi-source surveillance at both national and provincial levels as response decision-making requires data and access to information. Surveillance and response strategies may be adjusted at the different stage of COVID-19 transmission.

Vigilance for the future

Even though Cambodia has so far contained the virus from spreading within its borders, it remains vital for the country to be prepared for the continuing response to COVID-19 as well as future health threats in Cambodia. The risk of COVID-19 spreading in the country remains high as importations are still possible, since many other countries have ongoing community-level transmission. The pandemic is far from over – it will only be over when the whole world has stopped transmission. This means that we must continue to strengthen the core public health system and health care readiness during this window of opportunity before a future wave. Focus areas for the near future are: points of entry such as airports and land border crossings; expanding respiratory diseases surveillance; enhancing laboratory, surveillance and response capacities at provincial, district and community levels; and continuously improving risk communications as the situation evolves.

As highlighted by the WHO Representative to Cambodia, Dr Li Ailan, in her recent remarks, “The people of Cambodia should be aware of three important things. Firstly, be vigilant. Secondly, be a champion for the “new normal” and lastly, be ready for emergency response in the future.”

Cambodia is still at the early stages of the COVID-19 epidemic, and is making efforts to prepare to respond to larger scale outbreaks of COVID-19. Working together, WHO and the RGC seek to minimise the health, social and economic impacts of COVID-19 on the people of Cambodia, through investment in a stronger heath system including the core public health surveillance and response system.

Key Contact: Asheena Khalakdina

Title: Country Team Leader

Contact: khalakdinaa@who.int

Original article from: WHO World Health Organization